Wozdle, the best game for the Apple1 (Wozdle 1/3)

This is the first of a series of post on Wozdle. In this part we will explore the idea, and see how it is feasible to create a perfect wozdle clone on the Apple 1. The others posts are part 2, where we will discuss the UX challenges that the Apple 1 introduces and part 3, where we will describe the implementation.

I recently got an apple 1, and it quickly became my favorite computer.

This started about 6 months ago, when Antoine, aka SiliconInsid started to build a handful of brand news Apple 1 and asked me if I wanted one. I would have never hoped for such opportunity, and I'm forever grateful. Also, I was intrigued, because I thought maybe we could do some nasty software hack (short answer: unfotunately not, maybe more on that in a future blog post).

My apple1 is as close to the original as possible, uses the same components, often from the same time period. For all matter, I have an Apple 1, it was just built 47 years too late. It may not be exactly true, but it is close enough for me. Thanks Woz. And thanks Antoine.

And frankly, the look of the machine is sick.

So, Antoine is also building a ROM card for it, so I started scouring the internets for software, but, to be honest, I found the result to be quite underwhelming. There is the great 30th anniversary demo, that displays Woz, Jobs, but not much more in term of "interesting" software. The set of every machine language games and demos is totalling 150Kb...

I decided to stop complaining and create something to showcase the machine. A game. A known game, that could be used to demo the machine to unsupecting users. A game to show the machine to non-nerds.

This is how Wozdle was born, a perfect Wordle clone for the Apple 1.

It took around two days to code, and I am pretty proud of the result (it took me 3 months to make this blog post -- that's another problem)

But there were 3 challenges to overcome. Designing the game algorithms, designing the game UX and implementing it. We'll be focusing on the first item, the other twos have their own post.

32K ought to be enough for everyone #

The original Apple1 had 4K of RAM, extensible to 8K (like mine has), and could even be upgraded to 48K. There were two ways to load software:

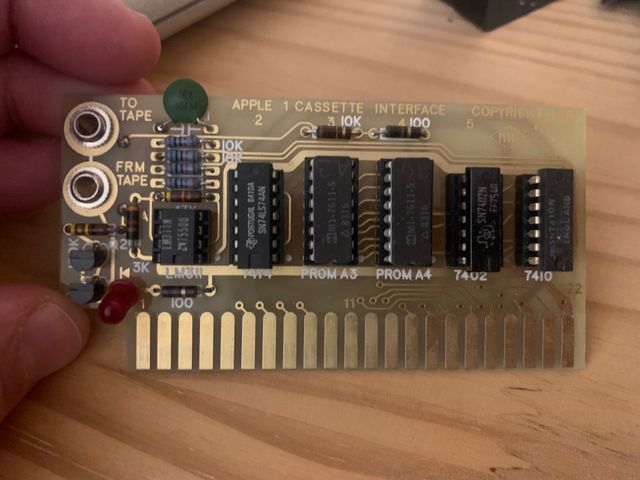

One way was to use the cassette card and a cassette player:

The cassette interface was notably hard flimsy, and slow. At 1200 it would take around 4 minutes to load wozdle. Also, the code loaded from the cassette is loaded to RAM, so you need as much RAM as code you have. Most Apple1 have 4K or 8K of RAM.

The other way was by having the software on an EEPROM (like the Integer BASIC ROM above) and executing it "in place" (meaning that the code is not copied into the RAM for execution).

This is pretty close to what a game console cartridge is.

So my goal is to put in in the ROM. As Antoine's ROM card gives 32Kb of addressable ROM, there should be plenty of space, right?

Let me describe the rules of Wordle: the computer choses a 5 letter word from a list of 2309 words (called answers). At each turn,the user enters a word, and the computers displays which letters are correctly or incorrectly placed, a clear inspiration from the old Mastermind game.

However, the user cannot enter any combination of 5 letters, he has to enter a valid word. And this is where Wordle gets it perfect: the list of acceptable user words (the vocabulary) is larger (12947 words). This enables wordle to know all the 5 letter words, but only choosing from the simplest ones, limiting user frustration. This is brillant game design.

But that also 12947 5-letters words. That's already 64735 bytes.

Or is it?

Encoding words #

Let's try some compression. In developing wozdle, I created a C++ companion program that helped me to try ideas, compute sizes, etc. You can find it on the github.

For wozdle, compression is all about using something we know in our data to encode information more efficiently.

First, we can exploit the fact that a byte can store 256 letters, but only have 26 of them. 3/8th of the bits are just zeros! Let's code the letter on 5 bits, and we can code a word on 25 bits (technically, as log2(26^5) is around 23.5, we could code the words with 24 bits, but that would require me to implement a division by 26 in 6502 assembly. And I don't want to)

So, from now on, our words are numbers. 'A' = 1, 'B' = 2, expressed in base 32. This means that 'APPLE' is 1, 16, 16, 12, 5. In base 32, we do (((1*32+16)*32+16)*32+12)*32+5. Of course, the reason I chose 32, is that the computation is trivial to do in binary:

A P P L E APPLE

1 16 16 12 5 1,16,16,12,5 (base 32)

00001 10000 10000 01100 00101 0b110000100000110000101 (base2)

0000 0001 1000 0100 0001 1000 0101 (idem)

0 1 8 4 1 8 5 0x184185 (base 16 -- hexadecimal)

In decimal, APPLE is 1589637. Note that choosing 'A'=1 and not 'A'=0, gives 'AAAAA' the value 108421. This was chosen to enable a small optimisation in the 6502 assembly code. In retrospect, I probably shouldn't have done that.

So, if we encoded the set of words as a bunch of numbers, we would use 12947*25 = 323675 bits, or a little over 40K.

Not good enough yet.

Encoding the 12947 word vocabulary #

When we just encode the list, we encode all the words and their order.

However, we just need the list of words and don't care about order. This means there is an opportunity to reduce the size by imposing the order. So, what about sorting it?

Now for a common trick. When working with a sorted list, it is generally easier to store the difference between consecutive elements. For instance, 'APPLE' is between 'APPEL' and 'APPLY', respectively 1589420 and 1589433. Instead of storing 1589637 for 'APPLE', if we keep the words sorted, we can just say it is 217 after 'APPEL'. And that by adding 13 to 'APPLE', we get the next word.

If we apply to the list for words, we get:

words: AAHED AALII AARGH AARTI ABACA ABACI ABACK ABACS ABAFT ABAKA ABAMP ABAND ABASE ABASH ABASK ABATE ABAYA

numbers: 1089700 1093929 1100008 1100425 1115233 1115241 1115243 1115251 1115348 1115489 1115568 1115588 1115749 1115752 1115755 1115781 1115937...

difference: 7299 4229 6079 417 14808 8 2 8 97 141 79 20 161 3 3 26 156...

It is obvious that the difference is smaller to encode. Let's look at it in hexadecimal, on 3 bytes:

00 1C 83

00 10 85

00 17 BF

00 01 A1

00 39 D8

00 00 08

00 00 02

00 00 08

00 00 61

00 00 8D

00 00 4F

00 00 14

00 00 A1

00 00 03

00 00 03

00 00 1A

00 00 9C

...

We easily see that all first bytes are zero, most seconds bytes are zero, and in may cases, a single byte is enough to encoded the difference. (There are 126 deltas that needs 3 bytes for encoding in the whole vocabulary), the largest one being between 'wytes' (24957107) and 'xebec' (25331875), and is 374768 (a 19 bits value).

At that point, we can take inspiration from UTF-8 and use the first bits to describe how to encode the offsets.

If the first byte starts with '0', we encode it on a single byte, with the first bit zero and the other 7 representing the number:

0-127, a 7 bits value, with bits a6 a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0, is encoded as 8 bits: 0 a6 a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0

128-16384, a 14 bits value, with bits a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0 b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0 is encoded as 16 bits: 1 0 a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0 b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0

16385-4194304, a 22 bits value, with bits a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0 b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0 c7 c6 c5 c4 c3 c2 c1 is encoded as 24 bits: 1 1 a5 a4 a3 a2 a1 a0 b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0 c7 c6 c5 c4 c3 c2 c1

To decode, it is easy: we read the first byte, if it start with a zero, the 7 rightmost bits are the number. If the second bit is a zero, then the rightmost 6 bits and the next byte are the number. Else, the rightmost 6 bits and the two next bytes are the number.

The previous offsets are then compressed to:

00 1C 83 => 9C 83

00 10 85 => 90 85

00 17 BF => 97 BF

00 01 A1 => 81 A1

00 39 D8 => B9 D8

00 00 08 => 08

00 00 02 => 02

00 00 08 => 08

00 00 61 => 61

00 00 8D => 80 8D

00 00 4F => 4F

00 00 14 => 14

00 00 A1 => 80 A1

00 00 03 => 03

00 00 03 => 03

00 00 1A => 1A

00 00 9C => 80 9C

Compare: 00 1C 83 00 10 85 00 17 BF 00 01 A1 00 39 D8 00 00 08 00 00 02 00 00 08 00 00 61 00 00 8D 00 00 4F 00 00 14 00 00 A1 00 00 03 00 00 03 00 00 1A 00 00 9C

and: 9C 83 90 85 97 BF 81 A1 B9 D8 08 02 08 61 80 8D 4F 14 80 A1 03 03 1A 80 9C

We went from 51 bytes down to 25, morre than 50% gain.

With these two compressions (representing words on 25 bits and encoding the difference of the sorted list), the 12947 words of the vocabulary are now encoded in 17903 bytes and the project become possible!

Encoding the 2309 words answer list #

Encoding the answer list of 2309 words could have been done with the same process. However, there are less answers, so the gap between words would be larger, requiring almost always 2 bytes. That would make the list a 4.5Kb data structure.

However, we know that the list of answers is a subset of the 12947 words vocabulary, so a simple bitmap of 12947 entries can work, and do the trick in 1618 bytes. I researched a couple of different optimisations, but didn't find something both simple and efficient (The most promising one was to add bit at the end of the vocabulary encoding, so words would be even or odd wether they are in the answer list or not. But it is not worth it, as all the offsets would increase, and the cost would be 1848 bytes).

While not extremely efficient for traversal, those two data structures are the core of the Wozdle implementation.

It is used at two different place:

-

At the begining, we pick a number between 1 and 2309. This is the guess the player must find. We then scan the vocabulary list and the answer bit map at the same time, ending when we have seen the right numbers of '1' in the bitmap. This gives the number associated to the word choosen by the computer, which we decode as 5 ASCII characters.

-

When the user picks a word, we convert it to a number and scan the vocabulary list until we find it, or the end. This enables us to validate if a word is in the vocabulary or not